A short, deformed little boy, wearing a hood and a monk’s habit, with silver buckles on his shoes: this is Monaciello, a spirit that appears in different forms, leaving coins in people’s homes when he likes them, and telling jokes that turn into numbers to play on the Lotto. He will hide and break objects or blow into the ears of people sleeping, simply out of spite. In her Leggende napoletane (1881), Matilde Serao says that this “munaciello” was actually a real person. It was in 1445, when Naples was under Aragonese rule. Two lovers had to keep their relationship secret because of the difference in their social class: she, Caterina Frezza, was the daughter of a rich merchant, while he, Stefano Mariconda, was a lowly servant. Every night, Caterina would wait for her beloved but one evening Stefano never turned up. On his way, he had been attacked and killed. The young woman was so distressed that she decided to withdraw to a convent where, nine months later, she gave birth to a sickly little baby, who remained that way as he grew up, humiliated by others. His mother prayed for him every night and allowed him to leave their home wearing a monk’s habit to bring him good luck. The little monk thus used to walk the streets of Naples and, upon the death of his mother, no more was heard of him. This is one of countless stories about the origins of Monaciello, the spirit that lives mainly among the deconsecrated churches and the small country vicarages at the foot of Vesuvius. One of these is the church of the Madonna dell’Arco in Pompeii, which for years was feared as it was considered to be haunted by the spirit. The church was founded by Nicola De Rinaldo, as a marble epigraph recalls, and for a long time rumours swirled about malignant presences inside the little building, precisely because of the ageing nobleman’s passion for spiritism. The building was one of the first religious complexes in the city and a custodian of its historical and archaeological past even before it was built, because it was here that the first discoveries of the ancient city were made. After the eruption of 79 AD the name Pompeii was no longer applied to a precise geographical location and, as from the Middle Ages, the place where the ancient city was buried began to be known as Civita Giuliana. It is here that the church stands, but no one knew that it marked the spot where the city was buried. Pagan religions and Christianity, spiritism and legends all weave together and survive in modern Pompeii.

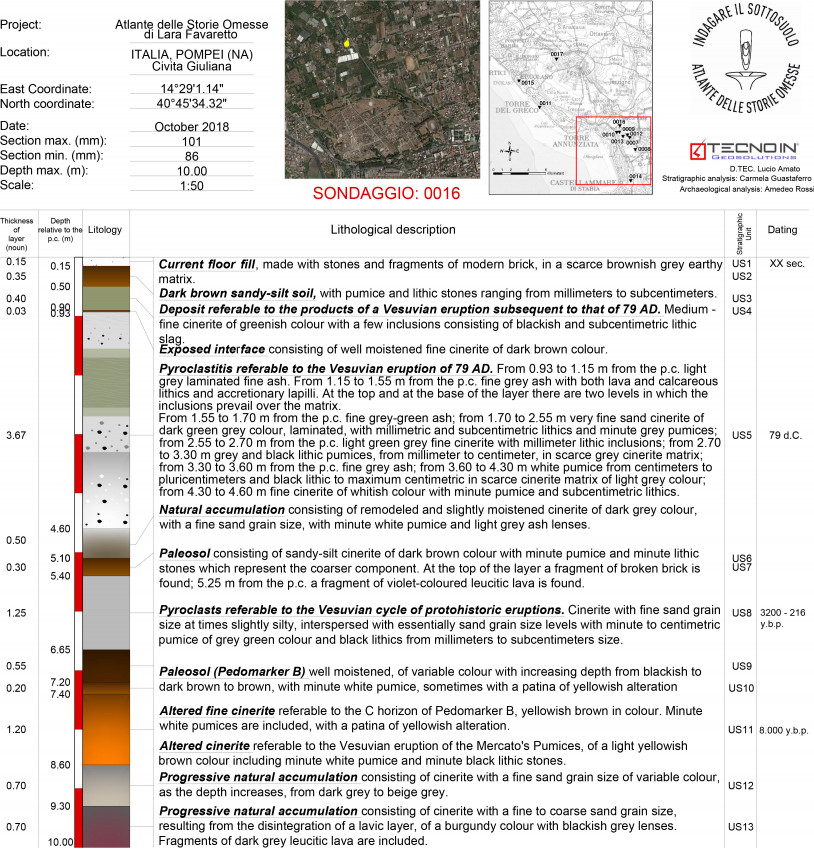

The 0016 core sampling site is in the municipal area of Pompeii, in Civita Giuliana. Unlike the coring carried out in the area of archaeological excavations, where the post-AD 79 stratigraphic sequence was removed in order to unearth the levels used during the Roman period, the 0016 core sampling goes through the entire sequence of products of the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 as well as through those of a more recent eruption, which is not clearly identifiable.

The Vesuvian pyroclastites of AD 79 are found up to 4.60 m below ground level, giving a total thickness of 3.67 m.

The sequence continues downwards with interbeds of eruptive products and levels that were altered and humified during the dormant phases between the various events. In particular, the products of protohistoric eruptions of Vesuvius are found between 4.50 and 6.65 m below ground level and those of the Mercato eruption at between 7.40 and 8.60 m.

At 9.30 m, down to the end of the core drilling (10 m below ground level), the alteration products of the lava substrate are found at the edge of the remains of the caldera of the Civita volcano.

The core sampling revealed no traces of human activity in the area, but in 1907 and 1908, in the area immediately to the north-west of the one examined here, excavations were carried out by Marquis Giovanni Imperiali, whose reports were published in 1994 with a monograph by the Soprintendenza. The old excavation had unearthed 15 premises in two sectors of the villa – one residential and the other for production. The residential area was built around a rectangular peristyle, surrounded on the north and east sides by an arcade supported by masonry columns, while the western side, which presumably made use of a natural difference in height, was bordered by a long cryptoporticus with a terrace over it, onto which the peristyle looked with a view across the land in front. Five rooms were found on the eastern side of the peristyle (the only ones that can be located with precision thanks to the photographs taken of the excavation). These were decorated with paintings in the Third and Fourth Style and contained a variety of objects for use in everyday life, and for personal ornament, and domestic worship. There is insufficient information to be able to locate the production sector precisely, but it was probably on the north-eastern side of the building. It consisted of a torcularium, a wine chamber and other rooms used for storing foods produced on the estate around the building. The location of a painted lararium on the south-eastern corner of the courtyard is also uncertain.

In subsequent years, other chance finds revealed further remains of buildings.