My mother had said it. I thought she’d said Farina – “flour” – and imagined she was talking about the plasterwork that, every night, would cause a little snowfall from the walls. I would try to blow it away, but that wasn’t the way to get rid of it, for I realised that this white dust would appear on the sheets in the morning, or it would be scattered over the floor. The house was always spotless, up to a point, so even just a few specks of dust immediately stood out. Sometimes I’d spit onto the dust and roll it into a ball, which I would hide in my trouser pockets and then throw out into the road on my way to school the following day. But when she repeated the word, it was clear she had said “Faria”. Abbot Faria, she had said. Or rather: “You think you’re Abbot Faria?” As she spoke, she leaned over my bed to have a closer look at the piece of torn wallpaper and a few inches wall stripped bare. You should leave it in peace, that wall, she said and then repeated the name, Abbot Faria, the little abbot, my little abbot, and she touched my head. I had very short hair back then, and felt her warm palm following the curve of my skull bones, and then again, on her way out of the room, she turned towards me but she was already talking to herself. Do you want to act like in the story? she said, spending years and years digging in order to escape? An instant later, she was already in the corridor, And where do you think you’ll go? We live on the third floor and what you are digging into is a perimeter wall. There’s the light well on the other side – do you want to dig all the way through the wall and then fall down? Or do you just want to dig? Her voice faded away as she reached the verb, but it carried on reverberating around my head like an echo – digging, digging, digging. Exactly what I really wanted: to dig, just to dig, the tips of my fingers gradually picking away at the wallpaper, with its synthetic fabric dotted with little blue and white squares, shaping the jagged edges to create different figures – a little house, a flower, little leaves, the head of a cat with pointed ears, but also bodies sensed, longed-for, and feared: genital monsters, but more than anything I wanted to reach beyond that double skin, that wallpaper and plaster. I wanted to end one surface and go on to the next, because behind one skin there’s always another. These surfaces never end. I would dig into one and it would appear to fade away, but actually it just contracted, healed, resurfaced, and sprang back out of itself. This was disheartening but also beautiful, because I adored the indomitability of the surface. I loved how my night-time venture never ended and so, after my mother had noticed the tears and scratches, I had continued. Every night, before falling asleep, I would scratch the wall as I lay down in bed. For five minutes, sometimes more. I never knew exactly how much time had gone by because I would fall asleep while digging, my fingers aching, their tips skinned. Little by little, the hole went in towards what my mother called the light well, but for me it was something else, something that mixed together darkness, the light in the well on the other side, emptiness, and solid materials that simply never ended. This was the spring of my ninth year, and when evening fell I became Faria. A few days later, my mother came back into my room – she never left the house but would always wander around it, always wearing a light dressing gown covered with pictures of carnivorous flowers, in both summer and deepest winter. She stretched out over my bed and looked at the torn wallpaper and into the hole. She took my hands in hers, passed her fingertips over mine, and then left the room. When I was on my own again, I realised that my mother never prohibited, never authorised, and really never even supervised me. My mother is what she is. She is there. She’s like the air, but she talks. I heard her footsteps again in the corridor – she was coming back – and her voice speaking to me, even before she entered the room. In the story, my still invisible mother said, Faria never digs with his fingers. Faria, my now visible mother said as she entered and came over to me, digs with this. She handed me a dip pen made of wood and steel, one of the ones that remained stuck in the pewter inkwell on the desk in the entrance hall. Then she touched my head with the palm of her hand and went out. I remained there with the nib in my hand, staring at its sharpened point, pressing it lightly against my fingers. That night my excavations were wonderful, and the tip of the pen made an animal-like sound as it pierced the plaster. Huddled on my side, I couldn’t see anything but I heard the sound of the digging. A sort of cri-cri noise that, in some places, where the plaster was damper, became a squit-squit. I dug deeper and, inside the wall, I heard a nocturnal cricket, a woodpecker, and a mouse. As I dug, I chased after the animals and tried to flush them out, but they always went deeper, hiding in the material. I tried to work out how far I still had to go, but that surface was always there in front of me. At a certain point, I thought those infinite layers would have to come to an end, so I tried to calculate how many more microscopic taps on the nib I would need to make in order to find, to extract, to come out on the other side. How many more scrapes were needed, and I felt the further I went the more something – a core, a meaning – would appear. I had to keep going but, at the same time, the kernel was being pushed further back, so I carried on – cri-cri, pic-pic, squit-squit – and without realising it, I fell fast asleep with the nib still in my fingers. I had dust from the plaster on my cheeks and nose, and I woke up in the morning tired, with my eyes dried out by the dust. I remained in a constant state of drowsiness in class that day, just waiting for evening to come. I had dinner, watched television for an hour and then went to bed. After my mother had bid me goodnight and turned off the light, I opened the drawer of my bedside table, took out my instrument and started digging again, moving the nib with my wrist and hand and fingers, gripping it as though I were writing, not a sentence that stretched out in space, but as an endless sentence penetrating it. I dug and I wrote, and there was no longer any difference between writing and digging. Then, one afternoon, I’d finished my homework and was sitting on the edge of my bed, with my back to the excavation. My mother came in, leant forwards and peered into the hole, the little flaps of wallpaper brushing against her cheek. I turned round to look. She stayed there, bending forward, one knee on the mattress, as though looking through the lens of a telescope. Then she sat down beside me. Looking at me in the eyes, she said Faria, what do you think you’ll find in there? I would love to have said I had no idea, but I didn’t have time as she immediately went on. Are you hoping to find a knife without a blade from which the handle has been stolen? I had no idea if she was telling me to continue digging with the knife we had in the kitchen drawer, the one with the broken handle, but that knife had a blade. I was about to ask her to explain but again she got in first. Think of a knife without a blade, from which the handle has been stolen, she said. I didn’t reply but looked at her – my mother made of air, with carnivorous flowers on her dressing gown. Think about it, she repeated, and without giving me time to say a word she asked What are you thinking of? and I nodded, but I wasn’t thinking of anything. See it? Can you see it?, and I said What? and she replied The knife without a blade from which the handle has been stolen, but in my mind I’d materialised a knife, and I was concentrating on the blade, but it wasn’t there, so I made it disappear. And then I moved to the handle, but that had been stolen, so I made that disappear as well. I tried again to see it but again I failed – the knife flashed before me in my mind and immediately disappeared. I turned round and looked at the hole, and then at my mother. She got up and touched my head with her hand, but when she moved away and left the room, it seemed to me that she had taken away the knife forever. In the nights that followed, my excavation plunged into chaos. Holding the nib tightly in my fingers, I scratched the plaster, chasing away the cricket and the woodpecker and the mouse, writing my sentence that pierced the material. But the knife without a blade from which the handle had been stolen suddenly came back to my mind and I lost my grip on the nib. I pushed my fingertips against the wood but only felt the nib dematerialising in my hands. The nib disappeared along with my fingers, my hand, and my wrist. I stopped excavating and remained there, lying on my back, with my eyes open in the darkness, smelling the dust in the air – the visible becoming invisible, matter immaterial – perfectly locked in my mother’s trap. And some days later, my mother reappeared at the door of my room. I knew she wasn’t really coming to me, but that my room was simply one more stop on her daily round of the house. I was just back from school and was sitting on the edge of my bed. She took a step towards me, then another, and another. She stopped in front of me. I raised my head and looked at the carnivorous flowers growing on the fabric. Faria, my mother said, how are you? I raised my eyes further: my mother was staring at me, her lips half open. It felt like it had been the flowers talking. I lowered my head. Faria Faria Faria, a flower had said. It was just a few inches from my face, all violet, with large petals, brown stamens, and it was gently swaying. It smelt of baking powder. How’s my little abbot? asked another flower, green and blue, How’s my little mole? added a gladiolus, How’s our little speleologist today? asked the carnation, How does my little core driller feel? came the question from an oleander flower, my baby carrot, You like baby carrot? The voices went on multiplying until they had formed a vast choir of plants, a constant murmuring – Faria Faria Faria Faria Faria – that shook the air like a puff of wind, an ever-louder buzzing noise that then suddenly stopped. The very moment the silence fell, I felt my mother’s hand, with her long, branchy fingers gently resting on my head. Faria, said my mother through the voices of all the flowers gathered together on her body, you have been digging and digging for days. You’ve dug and will continue to dig, because you like it, because you can’t help it. You dig so that evening will come, and when darkness falls you dig, you dig through the darkness to come out the other side, to smash it down and let the light pour in. You dig because you like moving your fingers, the way an insect moves its legs. You like groping, eating into the wall with your nib, and crunching it. You need to know that your excavation will not finish soon – it will last a long time and you’ll live a cave-life; you’ll see the day as a waste of light as you await the night, and when, at last, you will be able to lie down on your straw mattress – because that is what you’ll sleep on – and start digging, one millimetre at a time, you’ll slowly find your way into matter. Your beard will grow tangled, your hair long and white, your eyebrows a thicket, and you’ll dig and eat bread, and some fish, bones and all. You’ll make your own nibs, and with lampblack you’ll make your own ink, and you’ll write your book on the white fabric of your three coats. You’ll extract tallow from meat and burn it, you’ll preserve the fire you use to light your candles. And so, when you rest from digging, you will study until the flickering flame dies. You’ll never be lazy and you’ll learn five languages. You’ll know everything and it will be useless. You will be peaceful and stupid and nervous and ignominious and wonderful, and all will be useless. You’ll think you’re the heir to a treasure hidden in a cave, a cave hidden in the most secret part of the island and, as you dig, closed in your burrow, you’ll break the silence for a moment, exclaiming “this treasure” – hic thesaurus – and the nights will pass by under the flag stones of the walkway, always digging, stopping only when you hear, or think you hear, the sentries doing their rounds above your head. And you’ll spend another night, and the day will return with its wasted light and then again night will fall and you will wander through matter, until – and it is only right for you to know this now – you take a wrong turning and make a mistake. But you have no choice: your efforts are all wasted, just as all efforts are indispensable and wasted. Just as writing is always wasted. And so, after years and years of work, when you’ll imagine you’ve at last emerged on the other side, you’ll realise you’ve only gone from your own prison cell to that of another prisoner. You’ll escape by going inside, and never, never will you be given the outside. Never an exterior. The outside – cutting the canvas and escaping from the sack – is always, and only, the destiny of others. That’s what my mother used to say, the choir of flowers on my mother’s body, my oracular mother, my lying, feverish mother, visible and invisible, her hands on my skull, the warmth of her palms and then an ever-greater pressure, my mother’s fingers entering inside my head and coming out. My mother touching my cheek and withdrawing, with me looking at her hands, trying with my eyes to find the knife with no blade and its handle stolen. I can’t see it, it’s not there so it must be, it’s in her hands, it is materially immaterial, and then, at the door of my room, my mother stops and starts talking again. Faria, she says, all your life you’ll be a clandestine, and as an adult you’ll feel you haven’t just spent your time closed in a warren but hidden in the bowels of a ship silently sailing a black ocean. You’ll never know what goes on up there, high up, on the bridge of the ship, if someone’s still there or if they’ve all left, just waiting for clandestine life to come to an end. By now my mother was in the corridor and, before her voice disappeared, her last words were But you, Faria, keep on digging and digging and digging. So I opened the drawer of my bedside table, rummaged through it, and pulled out my nib. I turned and looked at the hole, remaining stock still. I tossed and turned in bed that night and then fell asleep. It was all a dream. In my dream I penetrated the wall and found it was not black, but white. It tasted of baking powder and, as I dug deeper, immediately below the surface I was scratching with my nib I could hear a light crackling sound, whispers, and rustlings. In my dream I knew it was the cricket, and the woodpecker and the mouse very slowly fleeing from me. Or maybe they weren’t escaping – maybe the cricket, the woodpecker and the mouse were just leading the way, together or scattered about, themselves seeking a crack through which to escape. Or they may even have just been playing. I was digging and they were playing, chasing each other, crazy and serene, through the dark blind matter. And, as I dug, I myself was the cricket, the woodpecker, and the mouse. I woke up very early that morning and, still in my pyjamas, went down the brightly lit corridor. There, on the Formica-top kitchen table was my cup. And, in the cup, steaming milk. I knew my mother was already awake – my mother never slept – but I had no idea where she was: at home, somewhere, because she was always at home, wandering through the rooms. I didn’t see her even after I’d washed, left the bathroom and gone back to my room, nor even after I’d dressed and prepared my satchel. My mother’s body was silent, somewhere around the house. When I was ready to go to school, I stopped by my bed and stared at the loose flaps of wallpaper, with the corolla immediately behind. I looked at the mineral chaos of my permanent worksite, the scratches across the plaster around the hole, each one a test. The tunnel ran deep, for what I saw was indeed a tunnel, the result of night upon night of work, nights and years, so many decades that I’d lost count of them all. Suddenly, in front of all that bare rubble, plain and naked, in front of that pointless destruction of plaster, dust and chippings, I felt an itch on my face. I touched it and felt my beard sprouting on my chin and cheeks. I touched it, and it was as hard as a clump. I stretched out to see it: it was as white as could be, and on my shoulders fell my long hair. This too was dry and rough. I touched my face and felt my cheekbones and forehead, my chalky skin and tangled eyebrows, and then I looked at my hands, my palms covered in lampblack. They smelt of wine. I’d have liked to look into a mirror, but I didn’t need to. I could see myself reflected in my hands and in space, in the humble ruins of my excavation site. Faria. I was Faria. The age-old, paradoxical child, the little ranter, Faria, the clandestine apprentice – and as I was feeling and thinking, and touched by the wreckage of my future, my mother came into my room. She put her hand on my head and ran her fingers through the thicket of my hair, then she took me by the hand and led me to the door of my room. Her dressing gown trembled lightly, its flowers gently carnivorous. As we went down the corridor in its blaze of light, I heard a noise and stopped, as my mother went on her way, calmly proceeding, lost in her rounds. I turned and looked back into the room, just in time to see the dust swaying softly in the air, the white cavern just above the bed, as the cricket, the woodpecker, and the mouse emerged. They looked around for an instant, and then swiftly disappeared back into their burrow.

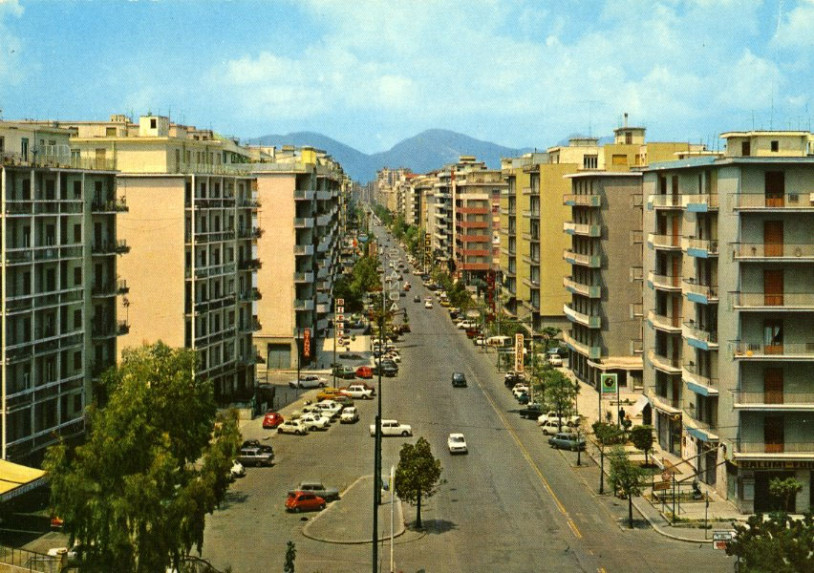

Via Sciuti, Palermo, Sicily. Photo taken between late 1960s and early 1970s.

Postcard of Via Sciuti, Palermo, Sicily, 1951.

Quartiere Libertà in Palermo, Sicily, a crucial place for most of the Mafia murders in the 1980s.