Whether or not the Villa of Augustus in Somma Vesuviana really was the last place to be visited by the founder of the Roman Empire, and whether or not it really was in these rooms that, on 19 August 14 BC, he was transfigured from man into demigod, is a matter that still today wavers between myth and historical truth. Ancient sources – the Annals by Tacitus and the Lives of the Caesars by Suetonius – state that Caesar Augustus was on holiday in Capri when his stomach, now chronically ill, was causing him excruciating pain. The emperor was taken to the “paternal villa” in the territory of Nola, where we are told he bore his agony with great dignity and good cheer.

Extract from Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, OUP Oxford, 2008, translated by Catharine Edwards

“On his last day, he kept asking whether there was any disturbance in the streets because of him. Asking for a mirror, he gave instructions that his hair should be combed and his drooping features rearranged. Then, when the friends he had summoned were present, he inquired of them whether they thought he had played his role well in the comedy of life, adding the concluding lines:

“Since the play has been so good, clap your hands

And all of you dismiss us with applause”

[…] He slipped away, as he was kissing Livia, with these words: ‘Live mindful of our marriage, Livia, and farewell.’ Thus did he have the good fortune to die easily and as he always wished.”

Historians and archaeologists turn to these chronicles, which contain a wealth of elegiac details, to study the emperor’s last hours and what happened immediately after. As in a theatrical script, we find the scene in which Augustus is concerned, first and foremost, with the state of the Empire and the wellbeing of its inhabitants. This is followed by his manly, stoically composed farewell, and his last, touching thought for his wife. Then come the funeral rites and the long procession of the coffin to Rome. This is the version handed down to posterity, and no new discovery is ever likely to break the idyll.

The disenchantment of our own age might bring to mind the title of the famous report on the bandit Giuliano written in 1950 by Tommaso Besozzi for L’Europeo: “The only thing we know for sure is that he is dead”.

The suggestion that the Villa of Augustus in Somma Vesuviana is where Augustus died was originally floated in the 1930s, based on the observations and studies of Matteo Della Corte, then director of the Pompeii excavations. He was working on a building, of which traces had emerged decades earlier, which was remarkable for its grandeur and richness, with magnificent pillars, fragments of polychrome stuccoes and capitals, columns, and statues.

In actual fact, what Della Corte saw – and what can still be admired today when the excavation site is open to the public – dates from some time after the eruption of AD 79. The interiors are indeed unusually rich for the area, and can justify the idea that they belonged, if not to an emperor, at least to a senator. This is what emerged from the discoveries made in the early 2000s, when the University of Tokyo – in the person of Professor Masanori Aoyagi, who later became the Commissioner of the Bunka-cho, the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan – organised the excavation in collaboration with the Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, thanks to the work of Professor Antonio De Simone. Given the huge quantity of references and representations of Dionysus among the finds, it is now believed that the building may have been linked in some way to the production of wine, an activity for which the whole area was famous in ancient times. Another intriguing hypothesis is that the palace, which was built on the ashes from the eruption of AD 79, was intended as a celebration of the rich past of these prosperous lands, and a return to happier times, as well as a wish for rebirth after all the destruction. The latest on the discoveries can be found on the website of the Apolline Project, a multidisciplinary study platform that devotes ample space to the villa.

Villa Augustea di Somma Vesuviana excavations

But why let the truth ruin a good story? All the more so when, as in this case, the story was used to promote Fascist propaganda. The news of the discovery of the last dwelling of the founder of the Empire, discovered practically by chance, was highly significant for Italy in the inter-war years. It was almost as if Providence – the same metaphysical entity that had already placed Benito Mussolini at the head of the government and plastered streets and buildings with ancient symbols, regimenting the Italians with rituals, greetings, legionaries, cohorts, and civil and military squads from childhood onwards – were now giving Italy and Fascism clearly established historical roots. Almost a blessing from the past, buried beneath the ashes of Vesuvius, awaiting a future generation that would at last be worthy of receiving it.

Excerpt from Alessandra Tarquini, “Il mito di Roma nella cultura e nella politica del regime fascista: dalla diffusione del fascio littorio alla costruzione di una nuova città (1922-1943)”, Cahiers de la Méditerranée 95|2017

Rome became the myth that inspired Fascism [...]: the living inspiration for a civilisation that could adopt, translate and present the symbol of a universal spirit in the world. [...] A militia was established in December 1922 along the lines of the Roman army: a police force divided into squads. Each squad was commanded by a squad leader and by two deputy squad leaders, called decurions; four squads formed a centuria, which was led by a centurion; while four centuriae formed a cohort, led by a senior; lastly, between three and nine cohorts could form a legion, commanded by a consul. Little did it matter that some of these terms had no precise equivalent in Roman military terminology: from that point on, the process of spreading the myth of Rome had no end.

Whenever possible, a certain faithfulness to historical reality was ensured by organisations such as the Istituto di Studi Romani, which was set up in 1925 to promote archaeological, ethnographic and cultural research into the history of Rome. Meanwhile, the architecture of the Eternal City was being forced to respond to a millennial appeal.

Ibid.

To celebrate the myth of Rome, the Fascists did more than just spread the use of the fasces. Right from the 1920s, the regime started eliminating what it considered to be “incrustations of the past” and in 1923 they began demolishing much of the historic centre of the capital of Italy, presenting the task as a liberation of the sacred places of antiquity that had been desecrated by contemptible superfluous additions. […] The head of the government saw no intrinsic value in ancient history. In September 1931, when the governor of Rome reported to Mussolini, informing him of how concerned the historian and former minister of education Pietro Fedele was about the destruction of all the popular architecture that had survived from medieval Rome, Mussolini replied: “Carry on demolishing and, if need be, we will also demolish the sorrows of Senator Fedele, who is so ridiculously moved by a bunch of latrines.”

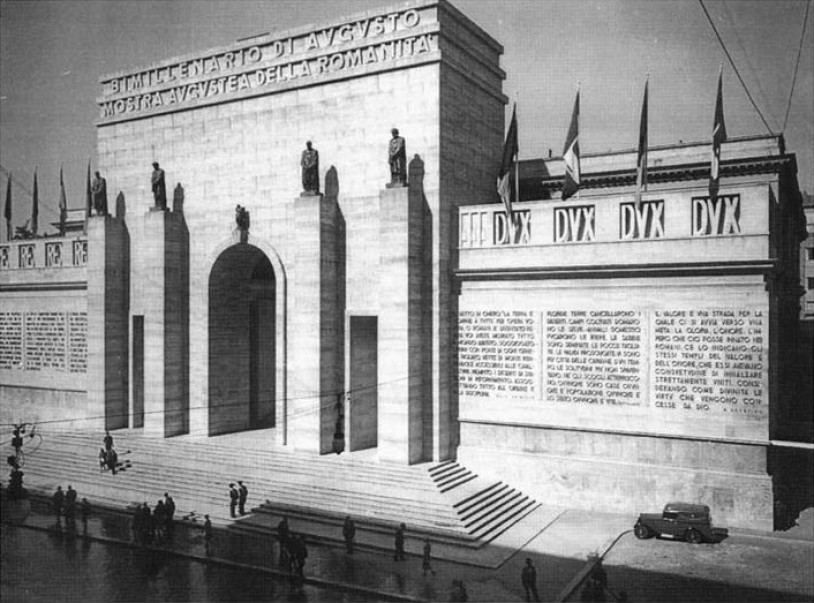

At the time when the villa in Somma Vesuviana was discovered, one of the most long-awaited events in the Fascist cult of the Roman world was to be the two thousandth anniversary of the birth of Augustus, which was set to be commemorated in 1937. The Istituto degli Studi Romani played a fundamental role in organising the celebrations, with exhibitions, Blackshirt parades, and conferences – from a historical and scientific point of view but also, and especially, it was to manage the funds that the regime had allocated for the occasion. The money would have been just what was needed to complete the excavation of the rediscovered villa, so in 1935, Mario Angrisani, the podestà of Somma Vesuviana, wrote a heartfelt letter to the head of the government, in the hope that, after the first chance discoveries, the excavations could start up again.

Starza della Regina excavations, Somma Vesuviana, 1930s

Excerpts from the letter sent by Mario Angrisani, the podestà of Somma Vesuviana, to Benito Mussolini, on 13 March 1935

Your Excellency,

Forty years ago, while transforming the cultivation of the Starza della Regina estate in Somma Vesuviana, a huge block of ancient masonry was excavated. By order of the director of works, explosives were set to blow it up: but, even though twelve of the eighteen mines exploded, the colossal ruin remained for the most part steadfastly and imperiously in place. The destructive enterprise was abandoned and thick brambles invaded the trench.

In the seventh year of the Regime, the vast estate was sold off in small plots and the farmer who bought the plot with the ruin cleared the ditch of its brambles and continued digging in order to build a cistern. Before his astonished eyes appeared a face resting on travertine frames and, to the side, an aedicule above a triangular pediment.

[...]

This Imperial building buried at the beginning of the Flavian dynasty, when it must already have been over fifty years old, certainly dates from the Julio-Claudian dynasty, of which no other similar architectural structure is known, which only a complete excavation will reveal to the eager eyes of scholars and savants as the forthcoming celebration of the two thousandth anniversary of Augustus draws near.

[…]

We most certainly have before us a magnificent Roman monument, ignored by the sources and preserved by a massive stratum of mud. May we hope to discover the secrets it holds?

When writing these carefully pondered sentences, each carefully constructed to achieve its purpose, the author of the letter certainly imagined how the famous frown would appear on the Duce’s face as he read the message. He therefore constructed a text that, like a crescendo in an opera, would capture the reader’s complete attention and possibly even his senses. The podestà must have thought that, for once, it would be the Duce who would be caught in rapt attention as he read these words. The great Duce, who made those awe-inspiring proclamations from the balcony of Palazzo Veneto to the adoring, cheering crowds below. Paragraph after paragraph, with an ever more emphatic prose, the letter eliminated any doubt that the villa that had appeared before the peasant’s “astonished eyes” was anything but the one where Augustus died. It continued through to the closing lines, in which he openly made his request in all its obvious and, at this point, irrefutable urgency.

Ibid.

The citizens of Somma therefore present their ardent request to Your Excellency that you may deign to arrange for the appropriate and necessary financial means (which are included in the monies made available to the Istituto degli Studi Romani) to be given to the Municipality, and to other entities, to bring to light this magnificent, original work of Roman prowess, as the most important archaeologists in Italy and Europe have long desired!

It is humbly requested that Your Excellency, worthy heir to the spirit of Imperial Rome, turn your benevolent eye to these lands of ours, making this monument of supreme nobility, unlike any other in the world, gleam under our clear blue sky. Not only will it narrate in the loftiest manner the great love of the Duce for every vestige of the Supreme City, but, as part of the forthcoming exaltations of the genius of Rome and Augustus, it will be for the Nation, and for every conscious scholar, the destination of a dutiful pilgrimage this important relic of the life of Augustus.

Augustan exhibition of Romanity, Palazzo delle esposizioni, Rome 1937

However, Angrisani’s mistake, although he made it in good faith and in compliance with the procedures, was that the sent a draft of the letter to Amedeo Maiuri, a world-famous archaeologist and the powerful superintendent and director of the National Museum of Naples, as well as a consultant for the organisation of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità, an exhibition on Augustus and the Roman world, one of the events being put on for the two thousandth anniversary.

Maiuri was probably worried that a large portion of the funds would be diverted from other projects in Pompeii and he possibly also had some doubts about the villa really being the one where Augustus died. He therefore decided not to advocate on behalf of the citizens of Somma and of their podestà. He may have convinced Mussolini personally, or maybe he even prevented the letter from being delivered, but in any case he managed to ensure that the request was not accepted.

As a result, in 1937, none of the first Blackshirts, nor the scholars who were invited from across the world, nor the tourists or the inhabitants of Somma Vesuviana was able to enjoy what might have been – and almost certainly was not – the most sensational archaeological discovery since the March on Rome. It was only in the early 2000s, with the partnership between Masanori Aoyagi and Antonio De Simone, that new light could be shed on the site, which was free at last from any distorted propaganda view.

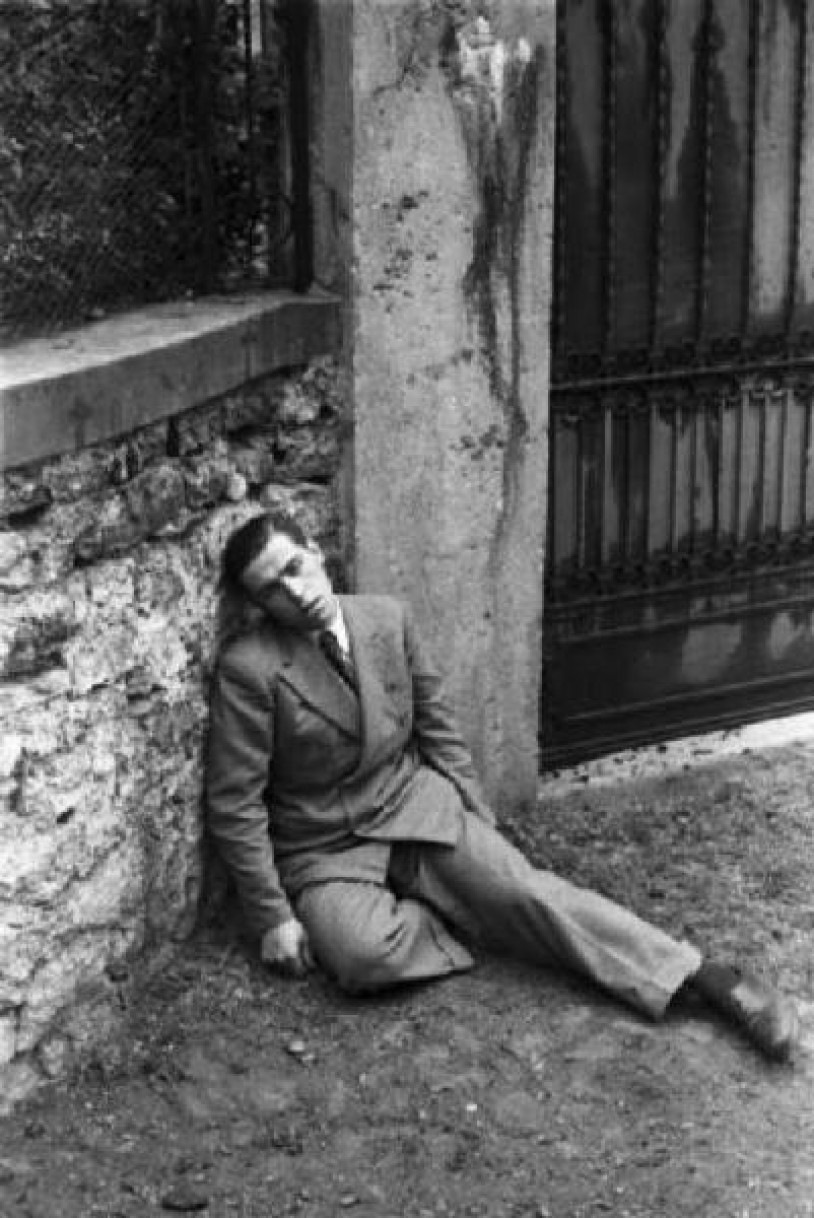

How does one tell the story of the death of a man who founded an empire, whether based on fact or for the purposes of Fascist propaganda? As we know, history is written by the victors. In 1947 l’Unità published a series of articles written by “Colonello Valerio”, the nom de guerre of Walter Audisio, the partisan who executed Mussolini’s death sentence in front of the boundary wall of an anonymous house in Giulino, in the province of Como.

Excerpt from “The execution of the dictator by firing squad”, in l’Unità, 28 March 1947

As soon as he set foot outside, Mussolini said, as he passed in front of me: “I offer you an empire”. I know that many people don’t believe this sentence was ever uttered, and it does appear incredible. And yet he said it: indeed, he said it with determination, with his famous headstrong attitude, that of a man who always keeps his promises. […] I suddenly started reading the death sentence against the war criminal Mussolini Benito. “By order of the General Command of the Volunteer Freedom Corps, I am tasked with doing justice to the Italian people”. I believe that Mussolini didn’t even understand those words: he just stared wide-eyed at the submachine gun pointing at him. [...] Not a single word crossed his lips: not the names of his children, nor that of his mother, or of his wife. He trembled, livid with terror, stammering through his swollen lips: “But... but... but Colonel...”. […] Not even to that woman [Claretta Petacci] who was hopping around near him and moving here and there, did he say a single word. No: he commended himself in the vilest manner, pleading for his big trembling body. That’s all he thought of: his big body up against the wall.

Bonzanigo. Bill and Pedro - reconstruction of the killing of Benito Mussolini. A man simulates the moment of death. Photo by Federico Patellani, 1945