But there is nothing there to be read or seen – except the mystery of one’s own image projected by the black mirror’s surface before it recedes into its endless depths, its corridors of darkness.

Extract from Truman Capote, Music for Chameleons, 1980

It was the evening of 19 September 2008. A few kilometres from the centre of Naples, where the Miracle of San Gennaro was still being celebrated – St Januarius’ blood fortunately liquefied again – a group of people decided to usher in the weekend by having dinner at a restaurant by the Lago d’Averno (Lake Avernus). The men were relaxed, drinking and eating and simply enjoying the fresh evening air. In the somewhat secluded restaurant, they were savouring the satisfaction of having done a good job, of having finally put an end to a tricky question in the best possible way. They chatted away, perhaps going back over the events of the previous evening. The gentle lapping of the water below them was faint, almost imperceptible. If not for a few slight ripples, the lake really would have looked like a vast, shiny black enamelled plate reflecting and immediately swallowing the very image of the diners. It was a late summer’s evening, one of those that make it easy to conjure up dreams and visions.

Charon ferried souls to the Underworld, whereas the Casalesi boss Giuseppe Setola met his men both before and after the death expeditions. This was the case after the Castel Volturno Massacre, on 19 September 2008, when the Casalesi mass-murder corps dined at the Aramacao restaurant. The previous evening, this hit squad had shed blood and caused terror in Castel Volturno. Seven dead, six non-EU citizens and an Italian, killed by 120 rounds from pistols and Kalashnikovs. The following day, Peppe ’o Cecato’s men feasted on the shores of the Avernus. And thus, two thousand years after Virgil, the lake was transformed from a classical myth to the theatre of a Camorra bloodbath.

“Sequestrato il lago d’Averno. Era in mano ai Casalesi”, by Vito Laudadio. Il Fatto Quotidiano, 10 July 2010

Police seizure operations at Lago d’Averno (Lake Avernus)

Peppe ’o Cecato’s mirage was a dream of domination that definitively evaporated in 2010, when the DIA – the Anti-Mafia Investigation Directorate – seized his clan’s assets. These included the lake itself, which until then had been registered in the name of a front man. This is just the latest in a series of illusions that have taken shape on those shores.

In the vast geography of liminal places dotted around all of southern Italy, Lake Avernus is certainly one of the most famous. Pages and pages have been written about it, ever since at least four hundred years before the birth of Christ. This was when the Greek historian Ephorus of Cyme wrote about how, among the tunnels dug beneath that area, there was a Phlegraean lineage of the Cimmerian population devoted to necromancy and the worship of an oracle of the dead. Above them, the waters of the lake released poisonous vapours into the sky: giving the lake its name, which derives from the Greek ά ορνος, “without birds”. Giuseppe Maria Galanti, an adherent of the Enlightenment from Campania, described how the lake exerted an influence on the “imagination of men”:

When the surrounding mountains were still covered in forests, this place was dark and shady and might have seemed dreadful, and the air one breathed would be heavy and damp and full of sulphurous fumes. It could be deadly [...] and it could satisfy the imagination of men with wonderful ideas of what they longed for. [...] In no little way did [the Cimmerians], real or supposed, help augment the horror of the place. It is said they were destroyed by a king of Pozzuoli to whom they had made a prediction, which unfortunately for them did not turn out to be true.

Extract from Giuseppe Maria Galanti, Breve Descrizione della città di Napoli e del suo contorno, 1792

Shadowy, poisonous and horrid, Lake Avernus has appeared in historical chronicles, and in literature and poetry ever since ancient times as the realm of deadly magic, from which only a few initiates have escaped unharmed. This was a view that lasted until the Enlightenment and, later, until the positivism of the nineteenth-century, which appear to have laid to rest the centuries-old legend that placed the mouth of hell itself right here. And yet, even then, its waters continued to reflect the “wonderful ideas” that human beings bring with them, forever a symbol of our constant fascination for the occult. And so it has remained: the lake appears to convey the image of each era in a shadowy, mysteriously and subtly negative manner.

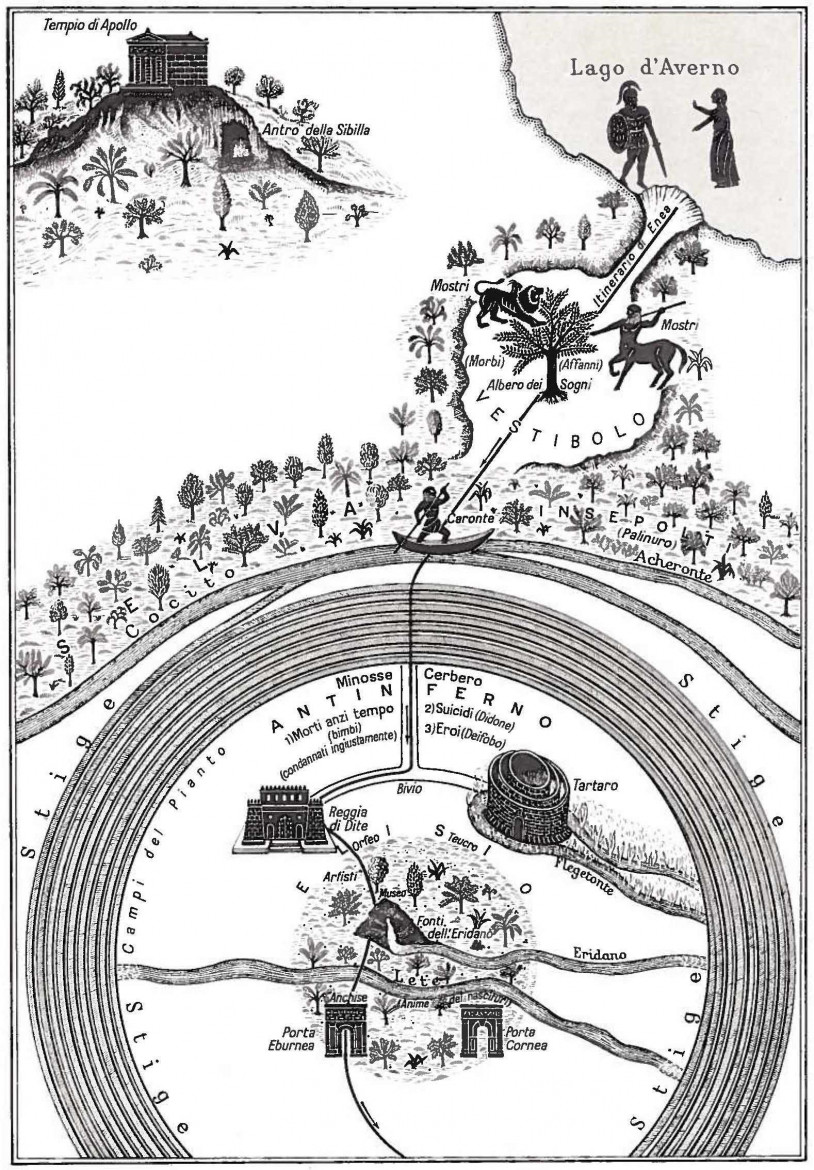

Virgil gave this place everlasting fame by making it the setting for the Aeneas’ descent into hell in the sixth book of the Aeneid. The Cumaean Sibyl points the way: “Trojan, Anchises’ son, the descent of Avernus is easy. All night long, all day, the doors of Hades stand open.” Among the rituals required for the enterprise, Aeneas needs to procure a golden branch: this talisman, which the hero finds near the lake, gives the title to the famous essay written in 1890 by the Scottish anthropologist James George Frazer.

When lo! as Morn her opening beams displayed, Loud rumblings shook the ground, the wooded hill-tops swayed, And hell-dogs baying through the gloom, proclaimed The Goddess near. [..] O silent Shades, and ye, the powers of Hell, Chaos and Phlegethon, wide realms of night, What ear hath heard, permit the tongue to tell, High matter, veiled in darkness, to indite. On through the gloomy shade, in darkling plight.

Virgil, Aeneid, VI

Map of Ade

Jan Brueghel the Younger, Aeneas and the Sibyl in the Underworld, circa 1630, detail. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The landscape that Virgil and his contemporaries had before their eyes must have been somewhat less sinister to look at. An artificial canal connected it directly to the sea, and it was used as the anchorage for the imposing Portus Iulius, the naval port complex built by Emperor Octavian in 37 BC. From then on, a series of events – not least the effect of bradyseism – gradually isolated it, taking it back to its original state. Its definitive detachment from the Tyrrhenian Sea came when the Monte Nuovo was formed by an eruption that devastated the area in 1538.

But the lake’s mythical fame has outlasted its history. Classical references brought travellers on the Grand Tour to visit it, and in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century it took on all the overtones of Romanticism. It is easy to be enchanted by the dark, murky waters that reflect the remains of ruined buildings such as the Temple of Apollo, which still today recalls the ruins painted by Friedrich. In 1853 the German writer Johann Gottfried Seume wrote:

The way to the Avernus is still quite romantic, but the entrance to the so-called Sibyl’s cave is really frightening. I stopped at the entrance and, looking to my right, I saw the ancient temple known as that of Apollo. By some miracle, it remained standing after the formation of Monte Nuovo, which cannot have taken place without enormous upheaval all around. One cannot imagine anything more romantic than the little passageway from Lake Avernus to the entrance to the cave, especially for those whose heads are filled with legends.

Extract from Fabrizia Ramondino, Dadapolis, Napoli al caleidoscopio, 1992

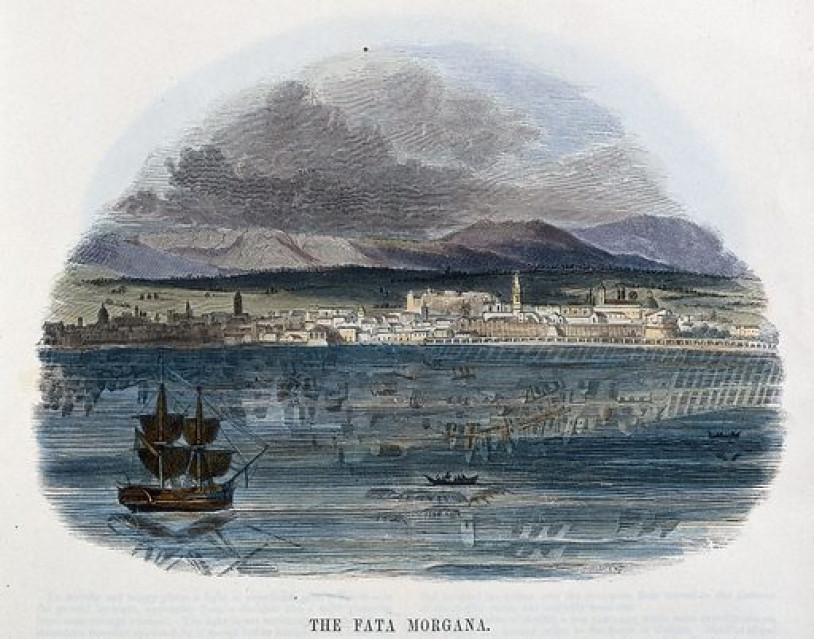

Evidence of the Fata Morgana on Lake Avernus dates back to the nineteenth century: this optical phenomenon, which is similar to a mirage, deforms the image of real objects and dramatically increases their size, reflecting them upside down or with rapidly changing shapes. The Fata Morgana takes its name from the famous Morgan le Fay of Arthurian legend, although the earliest records – such as that of the Dominican friar Don Antonio Minasi – state that the phenomenon occurs most often in the Strait of Messina. The presence of the Fata Morgana on Lake Avernus was reported by Marquis Giuseppe Ruffo, an ordinary member of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Naples.

Since we were on our way from Lucrino we were facing north, and our desire to hunt aquatic birds led us to the Avernus: but how astonished we were not to find the lake any longer where it should have been! At first I feared that my ability to see had suddenly waned: but when I peered at the surrounding objects, they came to me just as I had seen them a hundred and a hundred times before. Because, by warning me that it was but an optical illusion, the Fata Morgana rushed to both my mind and my lips: a voice that shattered the ecstasy and the astonishment of my partner. So what had become of the ancient motionless waters of the Avernus? They had been transmuted into meadows of fresh green, into beautiful trees tall and straight, into gently rolling hills. And all this swimming in an insubstantial cloud of ethereal silver dust.

Extract from E.T., Sopra la Fata Morgana del lago di Averno, 1834

The story continues with a scientific analysis of the possible causes of the phenomenon, as is frequently the case in writings of that time. From the end of the eighteenth century and for at least a century, the Fata Morgana was studied in geographical settings that ranged from the dunes in the Sahara to the expanses of polar ice, appearing in the chronicles of travellers, sailors and explorers across the world. Ruffo’s description, however, is not without a fantastical recollection, which also reflects those of his day. The image of the Fata Morgana – which is distinguished from the Arthurian sorceress by the fact that the name is always in Italian – appears in literature and music – in the title of an 1869 polka mazurka by Johann Strauss the Younger – as well as in theatre and poetry, with the 1873 poem of the same name by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and with Giosué Carducci’s Visione of 1883.

Charles H Whymper. Geography: a mirage in the straits of Messina. Wellcome Collection

Fata Morgana observed in the Sahara desert, south of the city of Tozeur, Tunisia

Today Lake Avernus has lost much of its magical charm, surrounded as it is by concrete structures and unauthorised dumps. The reflections that flitter across the murky, seemingly bottomless waters are no longer those that inspired scholars and poets in times gone by. One exception is that of the American poet Louise Glück, Nobel laureate in Literature in 2020 and the author in 2006 of a collection of poems entitled Averno. The book is inspired by the myth of Persephone, who is abducted by Hades who wants her as his wife in the afterlife, and it tells us of the restlessness of a young woman in her formative years, from her relationship with her mother to that with her lovers. For the seduction to be successful, also the Hades imagined by Glück appears to set up a Fata Morgana for the girl. Once again, the lake entangles and captures those who, when looking into its abyss, catch sight of the ghostly, fantastical projection of anxieties that are very close to them and well rooted in reality.

One summer she goes into the field as usual

stopping for a bit at the pool where she often

looks at herself, to see

if she detects any changes. She sees the

same person, the horrible mantle

of daughterliness still clinging to her.

[...]

When Hades decided he loved this girl

he built for her a duplicate of earth,

everything the same, down to the meadow,

but with a bed added.

Extract from Louise Glück, Averno, 2006

Lago d’Averno (Lake Avernus) and the temple of Apollo in an image of the early '900